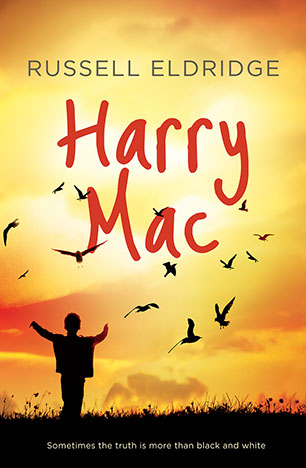

When Russell Eldridge retired after six years as editor of the Northern Star, he knew he wanted to write a book. The result is Harry Mac, a moving coming of age story set against the turbulence of South Africa’s apartheid. He talks to Verandah Magazine publisher Candida Baker about the book’s genesis.

Even if you had no idea that Russell Eldridge had ever been a newspaper man – there’s a dead giveaway, the moment you walk into his study. An absolutely utilitarian solid brown wooden desk, of the kind that populated the Fairfax and News Limited offices in the dim and distant pre-computer days.

“You’ve got it in one,” Eldridge says at my instantaneous guess. “It was the sports editor’s desk at the Sydney Morning Herald, and I was working at Fairfax when they were getting rid of them, so I put my hand up.”

The desk, which would have seen many thousands of stories cross its bows before it came into Eldridge’s possession, has certainly seen many since, but none quite as important to its owner has his most recent creation – his first novel, Harry Mac, which came about, he says, almost by accident.

“I’d retired as editor of the Northern Star,” he says, “and I’d actually written a crime novel. I was waiting to hear back from a publisher about it, and I was wondering what to write in the meantime, and suddenly the idea popped into my head. I think it had been sitting there in a little dark corner, but I’d never felt able to address it.”

The ‘it’ he is referring to his is childhood growing up in South Africa during the troubled years of apartheid, and Eldridge’s own experience of his father – the Harry Mac of the title, who was a newspaper editor and had been a POW in Italy during WWII.

“What I wanted to do was to try and distil the essence of those turbulent times,” he says. “When I was growing up in the fifties and sixties South Africa was a regimented society, a place which was still feeling the after-effects of World War II, and of the Boer War – there was the Secret Police, the Afrikaner Boers with their Dutch background, some of the Germans that were still on the side of the Nazis, and those of us from an English background who were caught in this middle-ground – seeing the oppression of the black population and at the same time living very comfortable lives that many of them did not want disturbed.”

The central element of the plot is that young Tom, Harry Mac’s son, overhears his father being told of a political assassination plot, and becomes terrified to think that his father is going to be caught up in what Tom is already sensing is a net of trouble closing in around not just his neighbourhood but the larger world outside.

For Eldridge, the plot was the pivot around which the rest of the book could grow. “It was actually based around the fact that our father had told us about a plot, but he’d dismissed it, but I began to think how that could play out as a fictional story, and that this was also around the time that Mandela was about to be arrested – he even hid in a house in our grandparents’ street at one point – and suddenly everything started to come together.”

It was the idea of how a child might have felt if he had imagined that his father was involved in something dark and dangerous that prompted Eldridge to use a child narrator. “It was liberating to use a child’s voice,” he says. “It allowed me to write about complicated things in a straight-forward way, with no adult baggage or cynicism attached. Of course, I had to pay a lot of attention to keeping up the child’s voice – not allow it to slip into using a more complicated vocabulary and at the same time keep it from being too childish.”

But young Tom has a way with words and a quiet observational skill – not unlike his creator. Working at the Northern Star with Eldridge when he was editor was a pleasure, although he says, he was not really cut out to be editor material.

“I moved to Australia in 1979,” he says. “My older brother had already moved to Australia, and my then wife and I were living near Soweto – close to the middle of the trouble spot for the riots, and I really felt it was time to get out. When we arrived I worked on the Sydney Morning Herald for a few years, and then I discovered the North Coast, and came up here to be a hippy in the hills which was good fun for a couple of years, but I gradually got sucked back into journalism, first of all working as a reporter and then as chief of staff.”

Eldridge was not, he says, automatic Northern Star editor material. “The Star was terribly conservative back in the day,” he says, “I really didn’t fit the bill. I was chief of staff for ten years before I was offered the editorship.” He found working on a local newspaper a rewarding experience. “It has its challenges,” he says. “You feel accountable to the people around you in a way that you don’t when you are working on big city newspapers, and of course it can often test your independence as a journalist.”

Something Eldridge took to heart however, was the importance of belonging to community, and for those of you who haven’t seen him act, he is a fine actor, as well as an active member of the Byron Bay Writers’ Festival Committee, and over the years he has immersed himself in many causes dear to his heart.

Some of the tests of independence Eldridge gives to Harry Mac as he struggles to make sense of the increasingly rigid regime bearing down on them – his mood swings and drinking affecting the Mac family, in particular Tom’s Mum, who treads around her volatile husband cautiously, trying – usually unsuccessfully – to prevent an outburst, or worse, a silent treatment that goes on for weeks.

‘I can’t help feeling the lane where we lived had something to do with it all. As though these families had been put there for a reason… it was so still, like everyone was holding their breath a lot of the time.’

Tom, however has an outlet for his worries – the lane in which he lives, which is populated with a cast of colourful characters, and most specifically his friendship with Millie, a girl slightly older than him. Tom and Millie have a bond – both of them are slightly physically disabled, Tom from the after-effects of polio, and Millie, whose neck is shortened. “I don’t know if Millie’s mother took thalidomide,” Eldridge says, “but I wanted to point to that time as being the peak era for thalidomide and polio, and how children with a physical disability were commonplace – and to create a connection between the idea of these damaged children, and the damaged system in which they were living. For me a central part of the book is the idea of ‘bearing witness’. That is that perhaps as a journalist or writer you are not always on the frontline, but it’s your job to observe and report – and I wanted to bear witness, not just to the dark politics of the day, but also to other, more personal issues.”

There was too, a personal connection with the idea of disability, since Eldridge has suffered on-going after-effects in one leg of an inherited condition similar to polio, although he has not let it stop him from climbing, even including hiking into the foothills of the Himalyas. At the house in Ocean Shores where he lives with his wife Brenda Shero, an artist, designer and writer, the couple have a kayak Eldridge frequently takes on the river, and it’s often, he says, when he’s out on the water that the next step in his writing will come to him.

Which leads me of course to the inevitable question of what he’s working on next. “To be honest the tank feels a bit empty at the moment,” he says, “but what I am very heartened by is the response from a lot of people who are saying they don’t want to let go of the characters – they want to re-visit them.”

In the mean time, of course, there’s always that crime novel sitting in the drawer.

Marele Day will launch Russell Eldridge’s book, Harry Mac at the Launch Pad at the BBWF on Saturday August 8 at 3.00pm. For more information on the Festival go to www.byronbaywritersfestival.com

Harry Mac is published by Allen & Unwin: https://www.allenandunwin.com/browse/books/fiction/Harry-Mac-Russell-Eldridge-9781760113209