The opening of the Tweed River Art Gallery exhibition, Arcadia Sound of the Sea, with John Witzig’s and Albie Falzon’s iconic images of the early days of Australian surfing mingled with painter Nicholas Harding’s pen and ink pandanus, contrasts beautifully with Michael Cusack’s latest body of work, The Same and the Other, writes Candida Baker.

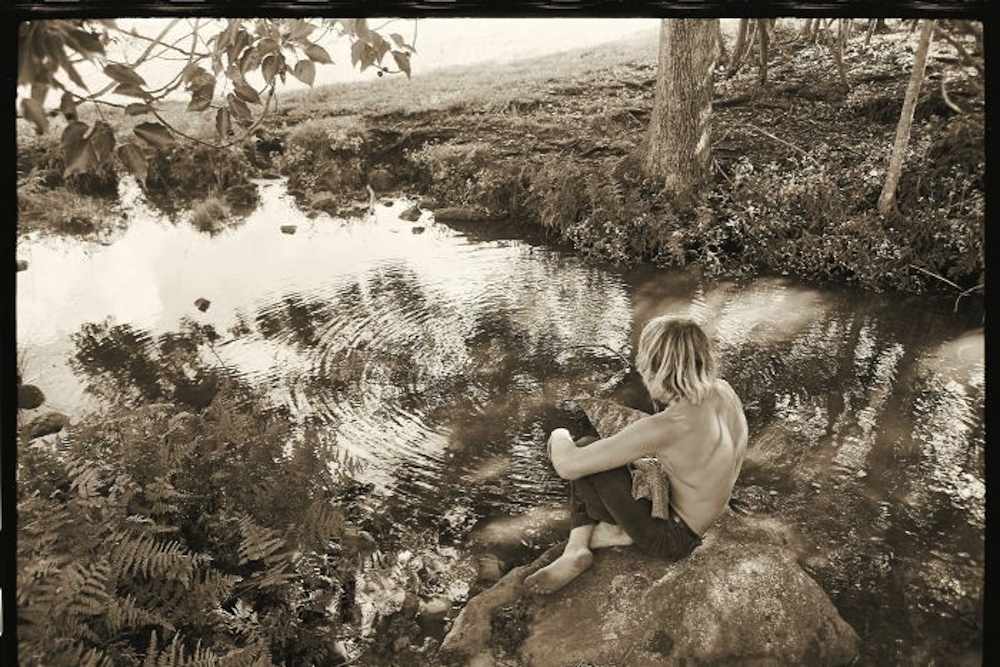

In one of John Witzig’s photographs, taken in 1969 at Possum Creek, near Bangalow not far from where I live, a young man is sitting on a rock, in the middle of the creek, poking a stick into the water which is rippling into never-ending circles. This quiet, contemplative image of a young Wayne Lynch, the teenage messiah of the shortboard revolution in the late 60’s and early 70’s, has a sweet nostalgia about it, and yet also a timeless quality. The creek is still there, the surfers still here, it’s not inconceivable to imagine this photograph being taken today. And yet, of course, what Witzig’s photographs, and Alby Falszon’s psychedelic film footage (which accompanies the photographs) do, is to sum up an era.

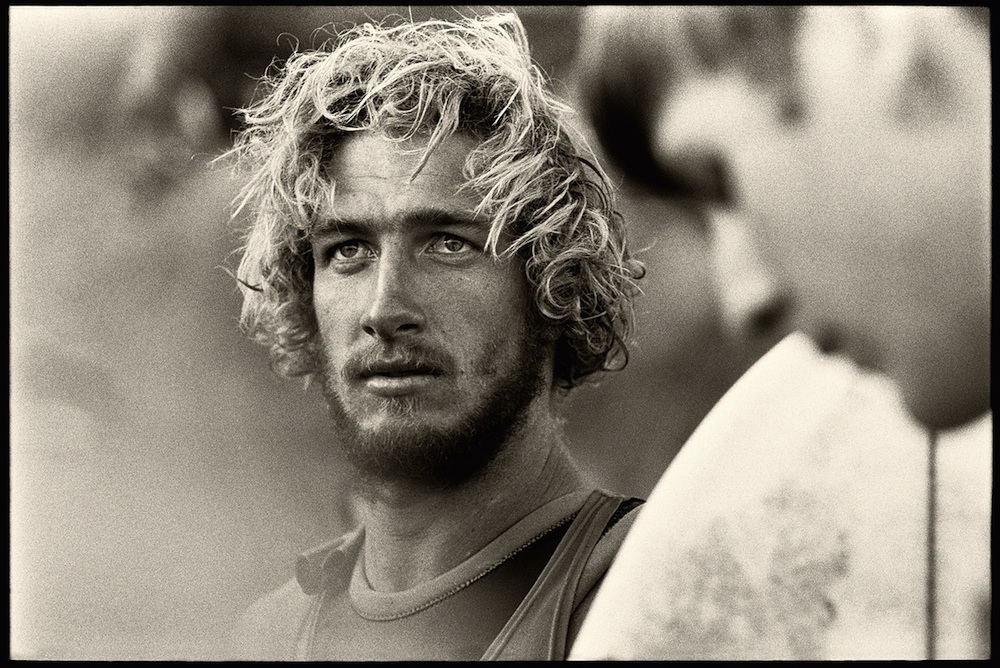

Looking at the exhibition, originally from the National Portrait Gallery, with an outsider’s eye, what strikes me immediately is the absolute ‘maleness’ of the photographs. This was a time when young male surfers could take off in their Kombi vans, living on next to nothing, and even, according to the surfer Nat Young, believing that: “by simply surfing we are supporting the revolution”. It was long before massive consumerism and marketing hit the sport, and when people-free waves still ruled.

In Sarah Engledow’s excellent catalogue essay, she too is drawn to the male energy of the photographs. The exhibition, she says, is “about how it feels to be lean, male, strong, untrammelled and irresponsible: to be a slacker with immense discretionary energy.” There is indeed, a kind of winsome innocence to the photographs, and an exultation in the sheer joy of being alive which was part, I think, of the appeal of Tracks, the magazine that Witzig, Falzon and David Elfick first put together one night in a house at Whale Beach in 1970, and which, of course remains the Australian surfer’s bible to this day.

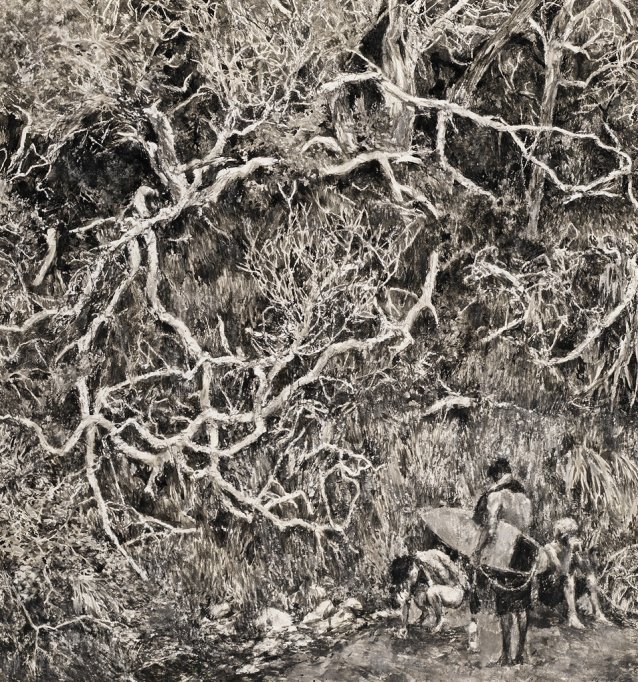

It was an inspired idea of Engledow’s to include another motif within the sounds of the sea – the massive, richly abraded, textural pen and ink drawings by Nicholas Harding of pandanus, that most coastal of trees, and used by generations of Australian beachgoers for shade, for somewhere to stand the surfboards, hang the towels, and stash the esky. These beautifully detailed works perfectly offset the ‘of the moment’ photographic and film works. Harding, originally from England, found solace in his drawing after the family moved to Australia, and has become famous for his textural use of paint, which is sometimes so thick on the canvas it creates an almost 3D effect – an effect also present in these pandanus drawings.

Harding’s drawings have a lovely connection to the Northern Rivers – introduced by his partner, Lynne Watkins to the Yuraygir region, near Angourie, and using it first as a holiday place, Harding gradually felt compelled to transform these fabulously messy, complex structures into drawings. Placed with careful intent between photographs, the provide a philosophical sub-plot which touches on our relationship to nature, on our mortality, and on a very different aspect of our relationship to the sea to the sweet simplicity of Witzig’s and Falzon’s photographs.

Next door to Arcadia Sound of the Sea in the Boyd Gallery is a very different exhibition – The Same and the Other by local artist Michael Cusack, a body of work which was inspired by a three-month residency Cusack spent at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris in 2014.

Cusack, like Harding, is from ‘elsewhere’, emigrating to Australia from Ireland in 1982, and until this exhibition, much of his work has had a strong connection to his homeland, with its never-ending supply of rock walls. Always drawn to shapes, Cusack has used a rock motif almost as a mandala for most of his work, re-working from the most muted of colours, to his later more vibrant works, the relationship between object, space and colour and becoming, in the process, a masterly painter of works that question a sense of place.

The Same and the Other sees Cusack’s normally large-scale works scaled down, a necessity, he says, of working in a tiny studio. The enforced need to rethink how he might portray Paris, has resulted in a wonderful exhibition, with Cusack’s trademark focus on fragments concentrated into an exhibition full of small delights.

Documenting the surface of the city, and collecting materials for his work, Cusack, it seems from this exhibition, dropped into that deep artistic space where inspiration and illumination bubble up to produce something surprising and unexpected, as in for instance, the wonderful piece, The Untold, a series of mixed media in old wide film canisters. The painted inserts give the canisters a contemporary abstraction and at the same time, have an almost negative quality to them, as if someone has dragged a piece of metal across a film.

According to Cusack, in this exhibition he was attempting to make forms that stand for themselves without explicit reference to an image, and yet somehow for the works to hold traces of Paris. He refers to Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s idea that “through attention I shall come by the truth of the object”, and suggests that he is looking for an impossible-to-find visual truth.

Having discarded my initial expectation of ‘big’ paintings, I found The Same and the Other a deeply satisfying experience. For me, having lived in Paris as a teenager, it was evocative as well, the tiny Parisian references creating glimpses of something larger – tempting the imagination to take the leap between the seen object and the remembered place.

I found it fascinating to contemplate all the works in these two very different exhibitions – on the one hand, the almost mystical recreation of a time of innocence in Witzig and Falzon’s work; the intense complexity of Harding’s drawings – all relating to an Australian coastal sensibility and Cusack’s work, in almost exact opposition, the minutiae of an European city revealed by a visitor searching for points of connection. This last, a connection to place, perhaps is also where a relationship exists between all the works in Aracadia the Sound of the Sea and The Same and the Other, whether it was almost accidental as in the cheerful documenting of the early surfing era, purposeful and fanatical as in Harding’s work, or a deeply absorbing process springing from exposure to new influences, as in Cusack’s – all of the works speak ultimately of where we’ve come from, where we’ve been, and where we might go next.

May we all, in our different ways, ride the waves of life.

Arcadia Sound of the sea and The Same and the Other are showing at the Tweed River Gallery until November 15. For more information go to: artgallery.tweed.nsw.gov.au

The gallery is open from 10.00 am to 5.00 pm Wednesday to Sunday.

![PastedGraphic-1[1]](https://www.verandahmagazine.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/PastedGraphic-11.jpg)