Candida Baker grew up in the English country-side – and death was a frequent caller. But in a tiny village it was not so much the loss of humans that introduced her to the transient nature of the universe but the fairly constant death of animals around her…

Death was there with the Siamese cats my mother loved so dearly – overly-efficient hunting machines, killers of voles and moles, and rats and mice and birds, often laid out in the bath for us to admire if we’d gone away for a few days. They were masters of a death stalk – silencing their bells, or even, on occasion hunting a hapless victim together. It was there when yet another of my beloved guinea-pigs went to ‘heaven’, sent there by an overly-zealous Golden Retriever, or lost forever when they escaped, or even, on occasions, when tiny babies were eaten by their own parents. It was there, most extraordinarily, when Daisy, the only Jersey cow in a herd of Friesian milkers, got old and sick and on the night she died the entire herd surrounded her, keeping a vigil for her, so that when the farmer went to see how she was, she’d peacefully left this life surrounded by her friends.

Somehow though, I was lucky, I passed my childhood and early adulthood relatively unscathed by the loss of those close to me – I had sat with my grandmother when I was eight, and held her hand only a few days before she died. She’d had a stroke and couldn’t speak, and for some reason I found it not at all scary – it seemed natural to me, and I’ve always thanked my mother for giving me the chance to say goodbye to her mother.

Local Byron Bay laughter therapist Ally Redding grew up without her Dad, and knows only too well how deep the well of loss can be. “My dad died of leukemia when I was four. My mum was left on her own to raise me and my three older siblings,” she says. “I didn’t fathom the enormity of that until I had my own husband and children. I never talked about my dad, I don’t remember him. My school friends never knew. I felt embarrassed when I had to tell someone my dad was dead, I don’t know why. I never saw my mum cry. We never talked or cried together as a family. I know mum did the best she could. That’s all we can ever do.”

For Redding, her mother was the rock of the family, for me, the reverse was true. Even though my mother had not died, I had lost her to alcohol by the time I was 14, although it wasn’t until I was myself in my 30’s that she died when she fell down the stairs three weeks before I was due to visit her, and then while I was in England for her funeral, my darling grandmother, my father’s mother, who had not been well, died before I could say good-bye, and I had loved her most dearly. Emotions in our family ran high for some time.

Mentor and business consultant Sonia Friedrich, who has recently experienced a family death, warns about the heightened reaction we can experience when someone dies. “Raw emotions rise around the passage of death. Feeling the love we hold for another person or another thing that is about to terminate can be too much to bear,” she explains. “In this heightened state, often accompanied by physical and emotional exhaustion, we may react rather than respond. It can occur in a manner we never knew existed or even felt before. In heightened states of passion we become a stranger to ourselves, no matter how prepared we’ve been for the on-coming death. It’s virtually impossible to interrupt this state once it has begun and it’s only after that we wonder, “what happened?” with time to reflect on the power of the emotions that overcame us. We hope nothing was destroyed along the way – in us or in another and for this reason it behoves us all never to grasp at the words that were spoken or what anyone says in these heightened states.”

“Deep grief sometimes is almost like a specific location, a coordinate on a map of time. When you are standing in that forest of sorrow, you cannot imagine that you could ever find your way to a better place. But if someone can assure you that they themselves have stood in that same place, and now have moved on, sometimes this will bring hope.”

― Elizabeth Gilbert, Eat, Pray, Love

For me my mother and grand-mother’s death seemed to set in motion a small tsunami of death – my step-mother was diagnosed with cancer of the spine and died shortly after my first child was born, one uncle died suddenly of a massive stroke, another uncle died, my father and my second step-mother left this world not so much at peace with it I would say, and all of this was in England – while I was here, on the other side of the world.

At the same time in my immediate life I was coping with those other smaller losses we face – the death of a family cat, the death of our darling 17-year-old dog, the death of a young dog from a tick, (and not with me, alone at the vet’s) the disappearance of an adopted cat and more. I witnessed first-hand the understanding of animals of death when a beautiful horse contracted pneumonia. The vet told us to get Fox out of the stable because if he died in there we would have to have him sawn up. He pumped him full of antibiotics but it was too late, and Fox paced our fences, touching noses with each of the other horses in turn. I swore I would stay up all night but finally had to sleep in the early hours and when I woke, on Mother’s Day, there he was on the arena, and I’ve never been able to forget that he had no one with him when he crossed over.

Now, I’m lucky, and I know it. I did not experience the physical loss of a parent when I was a child, or the death of my children, or partners, or sisters – or even as yet very close friends. I cannot begin to imagine how hard it must be to continue to exist when those who are an integral part of a daily life are suddenly no longer there.

But what I had (somewhat belatedly some might say) worked out was that all the losses I had suffered had been accumulating in me somewhere, and despite my deeply-held belief that the departed have simply slipped through the veil of illusion that separates us from the other world, I was sad, simple as that.

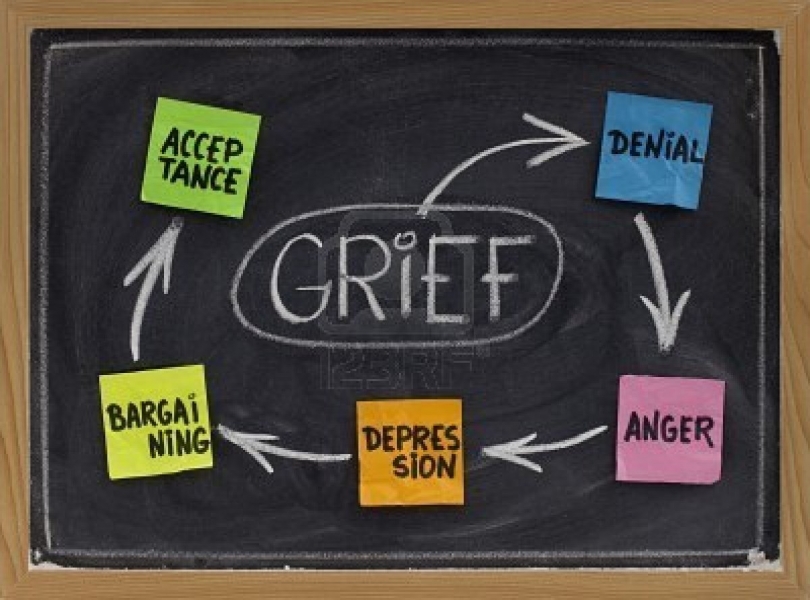

As Sonia Friedrich says: “We have to feel to allow the process of healing to take place. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross and her profound work with death and dying has taught us about our natural and powerful responses and in the process she’s really made acceptable the five stages of grief that define much of our behaviour. We really have to travel through them – the denial, anger, bargaining, depression and finally acceptance. There is never any need to rush your passage of grief. There is only one way to do it and that is in your own time.”

If someone mentions the idea of the Day of The Dead what immediately springs to mind (or to my mind at least) is the idea of Mexico and a huge full-on ceremony full of colour and movement, and yet somehow at the same time the name is confronting isn’t it? It’s simple and stark, and a reminder that this is our word for the end. So it was curiosity that this year I decided for the first time to go to the Natural Death Care Centre’s Day of the Dead celebrations at the Crystal Castle, mc’d by NDCC founder Zenith Virago, on whom I’d written a story the week before.

It was while I was driving there, thinking about life, death, the universe and everything, that I also experienced a revelatory moment – it occurred to me that although of course the physical loss of someone from our world is the most obvious manifestation of loss, many of us are also in far more grief than we might realise about what you might call life’s losses. The loss of several close friendships often weighs heavily on my heart, and all of accumulate these losses and disappointments through the course of our lives: the breakdown of a marriage, the loss of a job or home, or a change in finances, a miscarriage, the ill-health of a loved one, or our own, or the sudden disappearance of someone from our lives – these things (and much more) can haunt us.

Strangely – although perhaps not so strangely for those that know me – I remember when my father died only because our most beloved Shetland Pony, Sally-the-Boy, with whom we had shared family life for ten years, died one week short of a year later, of a brain tumour which had taken him in six months from the happiest little pony on the planet to a shadow of his former self. (But even towards the end Sally lived to eat – three times our vet came to put him down, and three times Sally, who could not by then even lift his head, had managed to get himself up and feeding again.)

Ally Redding married the man she started dating at the age of 18. In 2014 they separated, and as the initiator of the separation, Redding took on the feelings of responsibility. “I felt I should,” she says. “I felt I was responsible for the whole failed marriage thing. I thought I should be seen to be doing ok. But in the end even though it’s what I wanted, we are all grieving – all five of us – and other family members too, probably. We’re riding a roller coaster, and I hate those things!”

A psychologist told Redding she had ‘complicated grief’. “My response to that was like ‘No shit Sherlock’!” she says. “I have two special needs kids, and home-school one of them. One thing that had happened with me was that I’m not used to feeling pain – I’m an emotional eater from way back, from when my Dad died, in fact – and I’m having to learn to sit with the pain.”

Which begs the question what should we do with grief? Should we ‘put it all behind us’, ‘get on with it’, ‘pull ourselves together’ – or should we dwell on it, live with it, feel it, but in doing so perhaps allow it to affect our lives too much?

Everybody has their own journey through loss as we have our own journeys through life, but I think that the presence of ritual and ceremony can is a really vital part of a healing process, or as part of an ongoing acceptance of what we learn to live with.

It took me a little while, once I’d arrived at the Castle, to drop into a quiet space – it was all so beautiful, tables with clay on to make small offerings for a natural altar, pieces of beautiful paper to write messages on and hang on a message line, a surprising amount of friends to catch up with and chat to, that it wasn’t until all these pleasant distractions were over, and I was sitting by myself that I could really begin to feel why I was there. I’d come, I realised, just simply to allow myself the time to think about my parents, my family members and my animals – and also to think about those other losses, just as final in their way.

When Zenith started the ceremony, and the choir sang, I began to appreciate the true beauty of the gathering – that everyone there had experienced a loss, everyone there was gathered to bless those losses. Invited to say the names of their loved ones into the microphone, almost every single person began their litany – some of them seeming unbearable – a mother, a sister and a daughter lost to one woman. As each person announced the names of their loved ones, a we formed a circle, and as we did, a curious thing happened – a communal strength began to emerge – a silent acknowledgement that we had all, young or old, walked through this particular fire. At the end when Zenith asked us to touch the earth, and then the sky, to give a ‘whoosh’ of love for those gone from us, and the release was palpable. At its most basic level, we had been allowed to say it hurt, that death sucks when those you love are gone, and at the same time acknowledge the power of a group all holding the same intention, and for me the subtle presence of a presence greater than us.

It wasn’t masks and Mexico and giant ceremonies, but to my mind it was better than that – it was quiet time, reflection, an expression of love, and a place, finally, to take those losses, big and small, human and animal, and honour them.

You can contact Zenith Virago and the Natural Death Care Centre on: naturaldeathcarecentre

Sonia Friedrich is a mentor to business executives who wish to change their life. She has recently released “11 Steps to Healing – For Multi-Millionaires & Business Owners”. soniafriedrich

There’s an organisation called the Australian Centre for Grief and Bereavement. You can find them at grief.org.au.

Laughter therapist and retreat owner Ally Redding can be contacted on allyredding